Another Version of ‘A Christmas Carol’ — Why?

A lifetime ago, I left the suburbs of Philadelphia to become a boarding student at Milton Academy, a school so different from anything I knew that it might as well have been on the moon.

Suits at dinner? Amazingly, we wore them.

Toothpaste inspection? Yes, and your shoes had to be spit-polished.

Doing your homework in a communal study hall? Ninety minutes a night.

In those days, Milton – like many New England boarding schools – was staunchly traditional. Teachers were addressed as “sir.” There was a girls’ school across the street, but we had no co-ed classes. And before the prom, we rushed to get our “dance cards” signed by our coolest friends, so our dates wouldn’t think we were social outcasts.

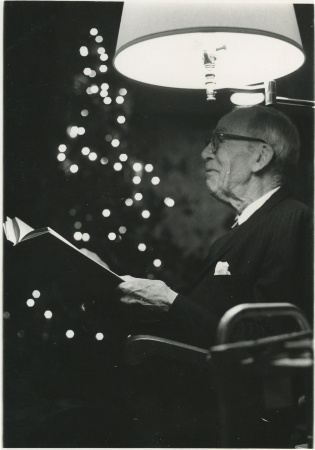

The library was the setting for the most memorable event of my first year at Milton – there, the night before we went home for Christmas, the headmaster read “A Christmas Carol.” Arthur Bliss Perry was as Old Boston as it gets. Son of a Harvard professor who discoursed on Emerson and edited the Atlantic Monthly, he came to Milton to teach in 1921 and became headmaster in 1947. In 1961, when I first encountered him, he was a figure out of time – a tall, thin patrician, wearing three-piece suits, a school tie and eyeglasses with octagonal lenses and the thinnest of wire frames.

The Milton library was a red-brick, ivy-covered cathedral. For Mr. Perry’s reading, the fireplace was lit. I believe we stood as Mr. Perry entered and took his seat in a baronial chair that had been set between the two standing lamps that were the only lights.

And then Arthur Bliss Perry became Charles Dickens.

He read without accent and without drama. He didn’t play up the sentiment. He simply delivered – as he had each December for fourteen years and would for two more – the greatest Christmas story since the original one.

I got shivers. Maybe a tear. It was that remarkable an experience.

Decades later, I decided our daughter was ready for a version of “A Christmas Carol” not dumbed down by Disney. I didn’t imagine I could equal Arthur Perry’s performance, but if an audience of adolescent boys counting down the hours until their liberation could listen in rapt silence to 28,000 words, I certainly thought our tot could make it, over two or three nights, to the end.

She lasted five minutes.

Some parents, at that point, would blame her near-total boredom with Scrooge on computer games and kiddie TV and an overly permissive culture.

Not this parent.

Books change over time, and over 180 years, “A Christmas Carol” has changed more than most. And that gave me an idea. If I wanted our daughter to experience “A Christmas Carol,” I needed to customize the text. My goal wasn’t to rewrite Dickens, just to update the archaic language, trim the dialogue, cut the extraneous characters – to reduce the 27,405-word book to its essence, which is the story. In the end, I did have to write a bit, but not, I hope, so you’ll notice; I think of my words as minor tailoring, like sewing on a missing button or patching a rip at the knee.

The “Christmas Carol” that awaits you is half the length of the original. Like the Paige Peterson illustrations that accompany it, it means to convey the feeling of London in 1843 without the formal diction and Victorian heaviness. It pleases me when adults tell me they have read it to their delighted children and when teachers write me to report that they’ve read it to students who were silent and involved. I’m especially pleased that kids, starting with my daughter, can read it by themselves with pleasure, right to the end.

– Jesse Kornbluth